Rapidly rising average temperatures and frequent extraordinary climate events make it hard to imagine a rethink of the drive towards a low-carbon future. But transitioning away from fossil fuels, as Julian Bishop, co-portfolio manager of Brunner investment trust, points out, is “an unprecedented multi-decade re-engineering of the entire global economy”.

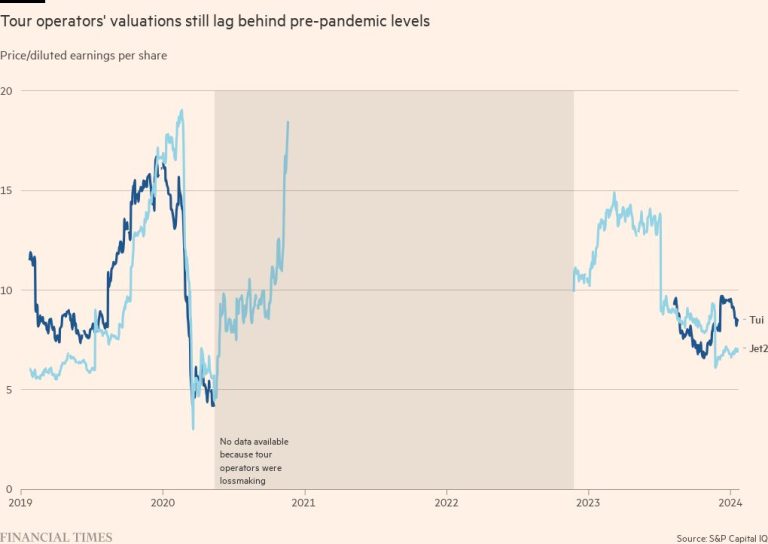

And there are certainly no guarantees of a smooth journey, as politicians face numerous conflicting pressures. For instance, the UK government has pushed back a ban on new cars with combustion engines by five years. Meanwhile, in Germany, the Building Energy Act “has been a bit disappointing in terms of timelines for phaseout of fossil fuel boilers,” says Fotis Chatzimichalakis, co-portfolio manager of Impax Environmental Markets investment trust (IEM).

Unexpected crises may also divert political attention and throw up competing short-term priorities — a prime example being the energy price hikes precipitated by Russia’s war on Ukraine. In that case, the disproportionate impact of higher energy bills on lower-income households in the UK pushed the issue of energy security back up the agenda, with plans for further investment in domestic oil and gas extraction announced by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.

But what do these short-term policy shifts mean for investors? Should they rethink their focus on renewable energy or seek to capitalize on new fossil fuel developments?

Mike Fox, head of sustainable investment at Royal London Asset Management, acknowledges that such interruptions to the shift to clean energy “can create short-term opportunities for investors in industries that had previously been expected to decline more rapidly, and indeed give more time for those industries to transition”. He cites conventional car manufacturing.

However, the long-term trend away from fossil fuels remains undiminished.

Ed Simpson, head of energy and infrastructure at Gravis Capital Management, argues: “While hydrocarbons will be required for years — both for power generation and as raw materials in chemicals industries — the science indicates that we need to wean ourselves off them, and to capture carbon dioxide where we do still have to burn them. This means there is no long-term case for fossil fuels in energy and transport.”

As a result, backing costly new fossil fuel facilities amounts to a risky investment proposition rooted in the hope that profits will flow before the assets become outdated and “stranded”.

Indeed, industry leaders, themselves, are keen to follow the prevailing direction of travel. When the UK government delayed the date for banning internal combustion engines, the car industry largely stuck with its plans for electrification, stressing the importance of policy consistency.

Simpson points out that, given the length of time needed to develop new products, “manufacturers are continuing with their plans for electric vehicles anyway, on the basis that consumers will be demanding EVs for cost, efficiency and environmental reasons regardless of government targets”.

At the same time, there are also compelling arguments for investment in the macro and “micro” infrastructure needed for a successful transition to renewables.

Kate Elliot, head of sustainable research at Greenbank Investments, maintains that many green technologies already cost no more than their higher-carbon alternatives and, in some cases, less — making them a doubly attractive proposition.

“The opportunities go beyond what many may think of as ‘green’ investments. . . to encompass areas such as upgrades to our energy transmission networks so they can handle greater electrification; rollout of connected systems that enable smart monitoring and management of energy systems; and energy efficiency measures in housing stock,” she explains.

One investment recently added to the IEM portfolio is in Prysmian, a company that produces electrical cables and fiber optics. Grid upgrades are needed not only to meet increased electricity requirements, but also to combat intermittency in energy generation and to distribute renewable power from where it is produced to where it is needed.

However, returns from investments directly into renewable energy, per se, have been disappointing of late, says Bishop. While the cost of producing the energy, itself, has come down, the challenges of solar and wind intermittency, and surplus energy storage, remain.

Battery storage, while attracting investors, is not necessarily the best solution. “Battery manufacturing is a capital-intensive commodity industry which itself is environmentally impactful,” Fox says.

Bishop agrees. Today, the best and most cost-effective way to store surplus energy is pumped hydro storage, he says. Excess energy is used to pump water up a hill [into a reservoir] and let it flow down again, powering a hydroelectric generator”, so that energy can then be released on demand.

Energy company SSE, liked by both managers, is not only reducing gas generation but investing heavily in a hydroelectric scheme at Coire Glas in Scotland.

At Gravis, Simpson favors diversification as an effective response to the challenge of unreliable renewable energy. As well as solar and wind power, the asset manager has exposure to anaerobic digestion (which generates energy from methane produced from waste) and “waste to energy” schemes.

Such an approach can also improve returns. “If we’re technology and geography agnostic, then we can buy the best assets — wherever they are,” Simpson explains.

But the asset managers show limited enthusiasm for nuclear energy solutions. At IEM, Chatzimichalakis steers clear, arguing that the financial and environmental costs of nuclear plants are still outweighed by the benefits of solar and wind power. “Technologies like small modular [nuclear] reactors have been ’10 years away’ for the past 40 years,” he observes.

Other managers concur that, while investment in new nuclear plants may be a significant aspect of a global green landscape, the UK public remains unconvinced. They see more popular, lower risk and cheaper opportunities elsewhere.

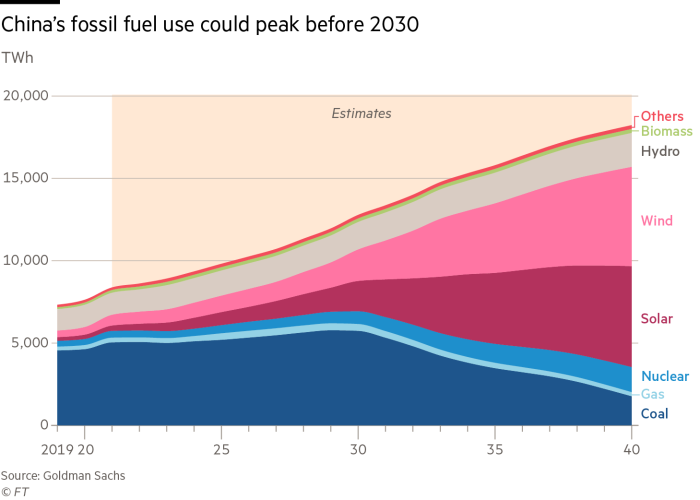

Nevertheless, Bishop accepts that it is not possible to generalize. “In France, where reactor designs were standardized, keeping costs down, nuclear power is a cheap and material portion of the energy mix,” he notes. And, more importantly, China — which is responsible for more than 30 per cent of global carbon emissions — is also now embracing the nuclear option to reduce its climate impact.

+ There are no comments

Add yours